It's Sunday afternoon and 10 people are gathered for a theater rehearsal in a community hall in Lille, a city in northern France.

Most of the amateur actors here did not get to know each other through the arts scene. They met during France's "yellow vests" protests.

The grassroots protest movement was at its height in 2018 and 2019 when protesters wearing yellow, high-visibility vests, blocked streets across France in response to fuel tax hikes designed to partially finance climate measures.

Since then the movement, named "gilets jaunes" in French, has dissipated somewhat. Smaller, local actions still take place but the larger protests have more or less ended.

But many of those who took part have not forgotten how it felt to belong to the movement. One of the actors here today, local 66-year-old woman Marine Guilbert, arrives at the rehearsal, a shiny yellow vest hanging out beneath her backpack. On it, the words, "fiere d'etre un gilet jaune," or "proud to be a yellow vest," flanked by two butterflies she painted herself.

One of the other actors teases her, saying she probably even wears the vest to bed.

'Even worse than before'

At the yellow vest movement's peak, some protesters rallied peacefully. Others threw smoke bombs, looted shops and burned barricades. French police pushed back with water cannons and tear gas, sparking accusations of police violence. According to data collected by French outlet Mediapart, the clashes resulted in four deaths and hundreds of injuries.

Seven years and many protests later, 66-year-old Guilbert is still angry about the political and economic situation in France.

"It's even worse than before," Guilbert tells DW. Her salary as a cleaner is less than €1,000 a month, forcing her to rely on money transfers from her son and food packages from charity organizations. She feels abandoned by the state. This is why together with this group, Guilbert is voicing her frustration in another way.

Guilbert can't remember when she last went to see a play. Too expensive, she notes. Now she doesn't need to see professional shows anymore, she says, and points to herself. "We were born artists," she exclaims confidently.

The Lille theater group only have a few more weeks to rehearse and meets at least once a week in a Lille community hallImage: Tessa Walther

The theater group was founded by Anne-Sophie Bastin, a lawyer and also a yellow vest from Lille.

"We have seen so much violence, injustice by police, that we have decided to reflect it on stage," Bastin explains why she founded the group, authors the scripts and serves as director too.

The group performed for the first time in 2019 and their play was about the yellow vests themselves. The new piece, which will be performed at the end of November in a 400-seat theater in Wasquehal, a town near Lille, is about Irishman Bobby Sands. .

A member of the anti-British paramilitary, the Irish Republican Army, Sands died on hunger strike in 1981, aged 27, while in prison. Seen by some as a hero and others as an extremist, Bastin says she finds him an inspiring figure.

As Bastin points out, out on the street the yellow vests were a leaderless movement. Here on stage, "they are not used to having a boss," she explains. Now she is the boss.

As one actor depicts his character according to his own interpretation of the script in the recent October rehearsal, Bastin intervenes in the rehearsal. "It is me who wrote this script."

In the past, only yellow vests were part of the theater group and at one stage, there were around 40 members. As members came and went, the group was opened up to friends and family too and now there are 15 members.

Anne-Sophie Bastin, the director of the theater group, says the leaderless yellow vests movement isn't used to taking orders, even from a theater directorImage: Tessa Walther

France in crisis

A new protest movement named "bloquons tout," or "let's block everything" in English, has largely taken the spotlight from the yellow vests in recent months as France lurches from crisis to crisis. A survey published by French newspaper Le Monde in mid-October found that 96% of respondents were unhappy with the state of the country.

One of the theater group members, pensioner Yolaine Jean Pierre, composed protest songs in her free time. On the day of the rehearsal, she wears a badge with a yellow vest and a red heart on her collar. When she strikes up one of her songs, the others sing along. Like a catchy tune, the melody and its rhyming lyrics remain in the ears. The theme is the same in all the songs: Blaming President Macron, the one whom they make mostly responsible for France’s situation.

This dissatisfaction is unlikely to be resolved easily. According to Julien Talpin, a political scientist at the University of Lille, France faces a structural problem.

"As the French political system is no longer able to address inequalities, anger is being expressed in other ways," he told DW.

One of the reasons for governmental instability is that President Emmanuel Macron lacks sufficient support in the French parliament to carry out reforms he says are crucial to solve France's economic quandary. French national debt stands at more than 100% of the country's income but successive French governments' attempts to curb the deficit — from reforming France's pension system to cutting national holidays — have faced a backlash from the public and political rivals.

A recent report by France's Inequality Observatory shows the country has seen an increasing poverty rate for 20 years.

Still, it's hard to see how changing the head of state would automatically solve France's political woes. If Macron stepped down, experts say he could be effectively handing France's top job to the far-right National Rally party.

A timeline of France's 'yellow vest' protests

French President Emmanuel Macron's concessions to protesters have not been enough to end demonstrations replete with violence and vandalism. DW takes a look at the chronology of the protests shaking France's streets.

Image: Reuters/G. Fuentes

Since his election in May 2016, French President Emmanuel Macron's popularity has fallen steadily thanks to unpopular financial policies, such as ending a wealth tax, and his public manner, which many see as aloof and arrogant. But it was his planned fuel-tax hike, an environmental measure, that really kicked things off. An online video saying Macron is "hounding drivers" goes viral in October.

Image: Reuters/C. Platiau

Online outrage is soon transferred to France's streets as more than 290,000 demonstrators don the high-visibility vests that drivers are required by law to keep in their cars. They block roads nationwide. The protests, coordinated via social media, have no structural organization, lack visible leadership and disavow union or party ties. At least one person is killed and more than 150 are arrested.

Image: Reuters/E. Gaillard

The Macron government says it won't back down, and further protests are scheduled. On November 24, some 100,000 people protest nationwide, with 8,000 in Paris, where violence and destruction breaks out. Police clash with protesters on the Champs-Elysees (above), using water canon and tear gas. Over €1 million ($1.1 million) in damage is reported.

Image: Reuters/B. Tessier

The "yellow vest" protests are a massive problem for Macron. He initially refuses to budge on the fuel tax, then proposes adjustment in case of rising oil costs. Not satisfied, protesters hit French streets again on December 1, with violence and vandalism erupting in Paris. Macron calls a crisis meeting the next day and on December 5, amid threats of more protests, Macron ditches the fuel tax.

Image: Getty Images/AFP/B. Guay

Macron, however, refuses to reinstitute the wealth tax and dismisses protesters' calls for his resignation. The "yellow vests" defy easy categorization, as protesters include both far-left and far-right supporters who opposed Macron's presidency bid. On December 8, nationwide violent protests take place again. Armored vehicles roll down Paris streets as much of the city goes on lockdown.

Image: picture-alliance/dpa/J. Mattiale Pictorium

On December 10, Macron responds to the 4-week-old protests with a televised speech to the nation from the Elysee Palace. More than 21 million viewers tune in as Macron strikes a conciliatory tone, saying he accepts his "share of responsibility" for the crisis. He introduces new financial measures, including a minimum-wage hike, tax-free overtime pay and tax exemptions for low-income retirees.

Image: Reuters/L. Marin

In the meantime, the "yellow vest" protests jump beyond France's borders to other countries. In Belgium, demonstrators expressed anger over high taxes and food prices, as well as low wages and pensions. Anti-riot police responded with water cannon after protesters threw rocks at the prime minister's office. In Germany, protesters also turned out in Berlin and Munich.

Image: Reuters/Y. Herman

Protesters in France continue into late December, though turnout numbers fall. That doesn't discourage unofficial but high-profile protest leaders, who use social media to encourage continued demonstrations. On New Year's Eve, many revelers wear yellow vests as they take part in peaceful, "festive" gatherings in Paris.

Image: Reuters/C. Hartmann

Any hopes for calm in the new year were quickly dashed when on January 5 a fresh round of nationwide protests saw some 50,000 take part, an increase in turnout after the holiday lull but less than initial December gatherings. In Paris, some protesters clashed with police, setting fire to motorcycles and storming government buildings. Macron condemned the violence, saying, "Justice will be done."

Image: Reuters/G. Fuentes

'Reclaiming' yellow vest protests

Several hundred women wearing yellow vests marched through Paris on January 6 in an effort to restore a peaceful image to the "yellow vest" protests. At one point during the march, the women protesters fell to their knees in a minute of silence for the 10 people killed and many others injured since the start of the movement.

Image: picture-alliance/dpa/C. Petit

In response to the "yellow vest" protests, Macron launched a series of town hall discussions where he said he would hear the concerns of the French. His first was on January 15 in the northern town of Grand Bourgtheroulde, where around 600 mayors from the Normandy region gathered to raise complaints from their constituents.

Image: Getty Images/AFP/L. Marin

Rubber bullets do damage, too

Prominent activist Jerome Rodrigues was injured in a confrontation on January 26. Rodrigues said he was hit in the eye by a police rubber bullet, an anti-riot weapon that has become highly controversial in France. The incident led to public outrage and was one of many severe injuries that protest groups blamed on the rubber bullets.

Image: Reuters/P. Wojazer

Court rules rubber bullets fair game

Following numerous injuries and outcry from the left-wing CGT trade union and the French Human Rights League, top French legal authority Council of State (Conseil d'Etat) refused on February 1 ban police from using the "sub-lethal" Defense Ball Launchers (LBDs) . The court said the risk of violence at the demonstrations made it "necessary to allow security forces to use these weapons."

Image: Getty Images/AFP/G. Souvant

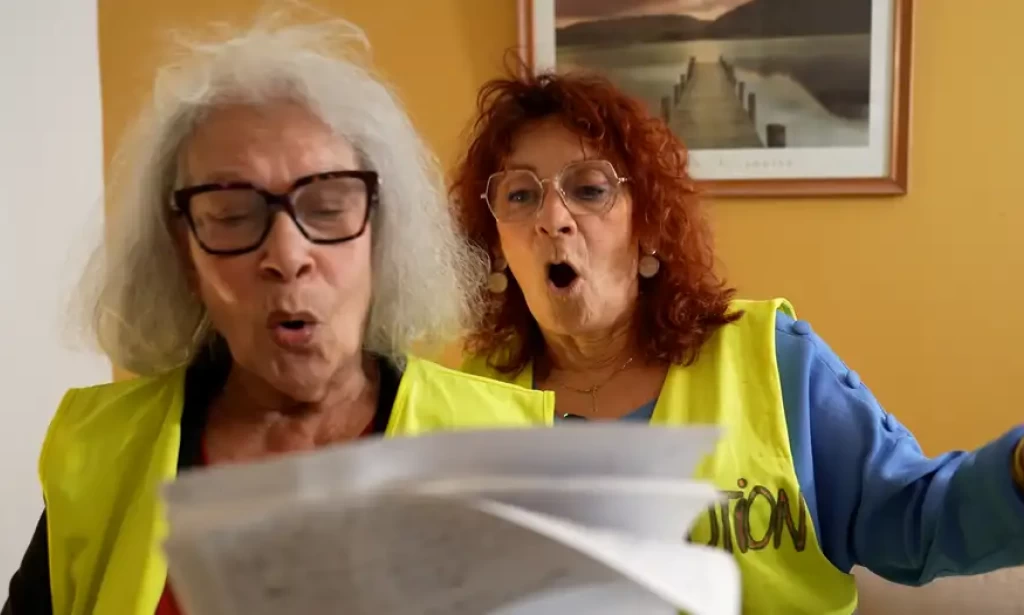

Lille locals Yolaine Jean Pierre (right) and Marine Guilbert (left) describe themselves as proud 'yellow vests'Image: Tessa Walther

You must be logged in to post a comment.