As South Korea’s only special self-governing province and a dual UNESCO World Heritage Site (Natural and Agricultural), Jeju Island rises from the East China Sea like a sculpted masterpiece forged by volcanic fire. Spanning 1,846 square kilometers, this oval-shaped island is the result of relentless volcanic activity that began 1.8 million years ago during the Quaternary period, with its last eruptions occurring 4,000 to 5,000 years ago—relatively recent in geological time. At its heart towers Hallasan, a dormant stratovolcano and South Korea’s highest peak at 1,947 meters, whose crater lake, Baengnokdam, glistens like a sapphire amid a carpet of alpine flora. Surrounding Hallasan are 360 smaller volcanic cones known as “oreum,” each with its own unique shape and ecosystem, creating a dramatic terrain of jagged lava fields, windswept cliffs, and crystal-clear crater lakes that dot the island’s landscape.

Jeju’s geological identity is inseparable from basalt, the black, porous volcanic rock that forms 90% of the island’s surface. This rugged stone has shaped not just the island’s geography but every facet of its culture, from architecture to spirituality. Along coastal roads and rural villages, visitors are greeted by traditional “seongeup” stone houses, with thick basalt walls that insulate against Jeju’s harsh winds and extreme temperatures—cool in summer and warm in winter. Dry-stone walls, built without mortar, crisscross the countryside, while the iconic “dolhareubang” (stone grandfathers) stand sentinel at village entrances, parking lots, and cultural sites. These stone statues, carved from single blocks of basalt between the 17th and 19th centuries, range from 1.5 to 3 meters tall, with broad faces, protruding eyes, and gentle smiles. Each dolhareubang boasts distinct facial features—some with furrowed brows, others with upturned lips—reflecting the craftsmanship of local stonemasons and the unique character of the villages they guarded. Originally believed to ward off evil spirits and bring good fortune, dolhareubang have evolved into Jeju’s most recognizable symbol, embodying the island’s spiritual connection to the land and its volcanic origins.

The island’s stone culture runs far deeper than aesthetics; it is a testament to Jeju’s resilience in the face of unforgiving geography. Volcanic soil, though rich in minerals, is thin and infertile, making traditional farming a constant struggle. To overcome this challenge, Jeju’s ancestors spent centuries carving stones from the earth to create arable land, developing an intricate network of “batdam” (field walls) that stretch over 22,000 kilometers when linked together—enough to circle the Korean Peninsula twice. Known locally as the “Black Dragon’s Long Trail,” these dry-stone walls were recognized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System in 2014. Beyond their practical function of dividing plots and preventing soil erosion, the batdam resolved long-standing land disputes among farming communities and protected crops from Jeju’s strong coastal winds, which can reach speeds of 50 kilometers per hour. Today, these walls still cradle the island’s famous citrus orchards, where Jeju mandarins—sweet, seedless, and bursting with juice—thrive. The mandarin industry, which accounts for 70% of South Korea’s citrus production, is a direct result of Jeju’s ability to transform harsh geological conditions into a sustainable livelihood.

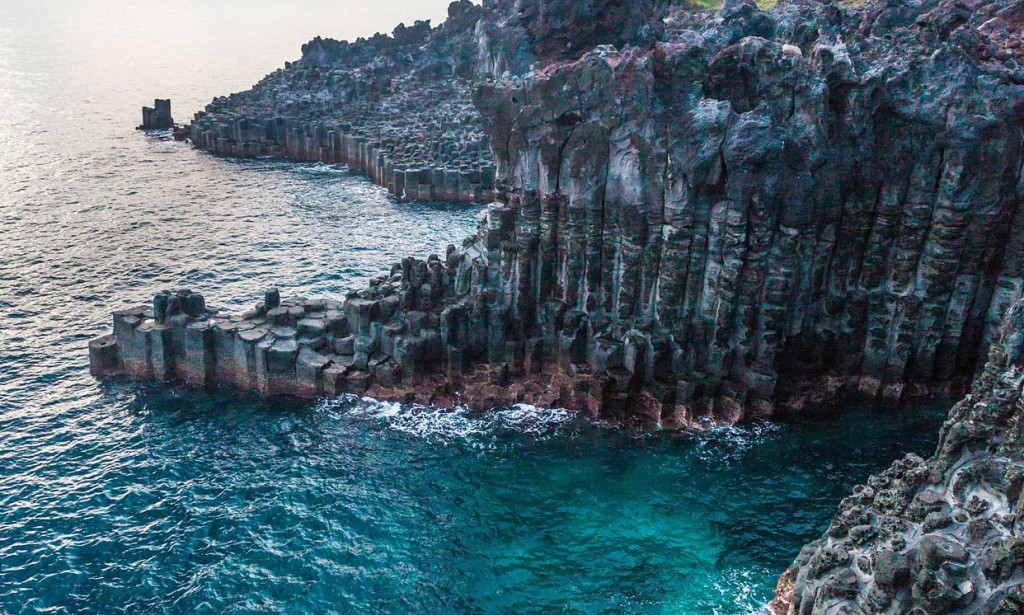

Jeju’s volcanic legacy is most vividly displayed in its lava tubes, among the world’s best-preserved and most extensive. Formed when molten lava from Mt. Geomunoreum—one of Jeju’s most active ancient volcanoes—flowed downhill, cooled, and hardened on the surface, leaving hollow tunnels beneath, these underground wonders offer a glimpse into the island’s fiery past. The Manjanggul Cave, the longest and most accessible of Jeju’s lava tubes, stretches 13.4 kilometers, though only 1 kilometer is open to the public. Inside, visitors walk along smooth lava floors past rare geological formations, including cave pearls—small, round concretions formed by mineral-rich water—and stalactites that hang from the ceiling like frozen icicles. Unlike limestone caves, where such formations are common, they are extremely rare in volcanic caves, making Manjanggul a geological treasure. Along Jeju’s coastline, volcanic activity has created equally stunning landscapes: Yongduam Rock (Dragon Head Rock), a 10-meter-tall basalt formation shaped by centuries of wave erosion, resembles a dragon’s head rising from the sea; Jusangjeolli Cliff, a 20-meter-high wall of hexagonal basalt columns, formed when lava cooled slowly and contracted, creating perfect geometric patterns that look like man-made pillars.

Culturally, Jeju is a tapestry of tradition, harmony, and unique customs shaped by its isolation and geography. The island’s most famous cultural heritage is the haenyeo (female divers), a community of women who have practiced free diving for seafood for over 2,000 years. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2016, the haenyeo dive without oxygen tanks to depths of up to 20 meters, collecting abalone, sea urchins, octopus, and seaweed. Historically, haenyeo were the primary breadwinners for their families, as men focused on farming and fishing in shallow waters. Today, the haenyeo community is aging—most divers are over 60—but efforts are underway to preserve their legacy through museums, cultural centers, and diving demonstrations. Another unique Jeju tradition is underwater stone tombs, known as “marae,” which are submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide. These tombs, dating back to the Tamna Kingdom (Jeju’s ancient independent kingdom), are believed to reflect the island’s animistic beliefs, which venerated the sea and land as sacred. Jeju Stone Culture Park, located in Seogwipo City, offers immersive experiences into the island’s stone heritage, with stone-masonry workshops, exhibits on the creation myth of Seolmundae Halmang (Grandmother Seolmundae)—who is said to have created Jeju by dropping stones from her apron—and statues of the 500 generals who accompanied her.

Jeju’s natural and cultural wonders are complemented by its laid-back lifestyle and unique cuisine. The island’s food is deeply rooted in its geography, with seafood and citrus taking center stage. Haemul jeon (seafood pancake) made with fresh catch from the haenyeo, hallabong (a large, sweet citrus fruit unique to Jeju), and black pork—raised on volcanic soil and known for its tender, flavorful meat—are local staples. Jeju’s climate, with mild winters and warm summers, also makes it a year-round destination: spring brings cherry blossoms and wildflowers to Hallasan’s lower slopes; summer is perfect for beach trips to Jungmun and Hyeopjae Beaches; autumn paints the oreum in vibrant red and gold; and winter offers quiet hikes and hot springs, or “jjimjilbang,” where visitors can relax in mineral-rich waters heated by volcanic activity. Whether hiking Hallasan’s well-marked trails, wandering through oreum-studded meadows, respecting the dolhareubang at village entrances, or watching the haenyeo emerge from the sea with their daily catch, Jeju is a living museum where geography and culture are inseparable. Every stone, every wave, and every tradition tells a story of resilience, harmony, and the enduring bond between the island’s people and their volcanic home.

You must be logged in to post a comment.