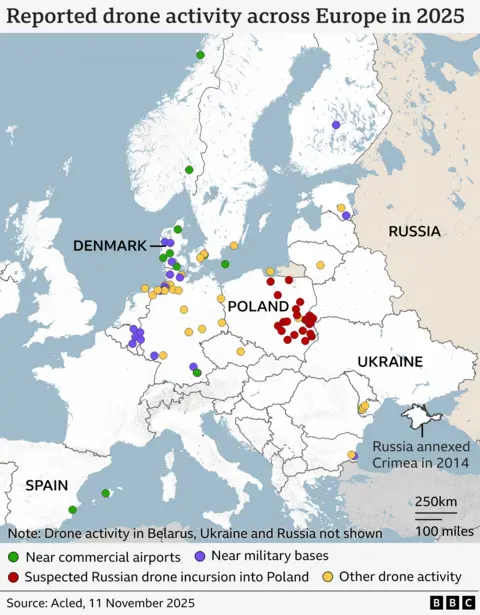

Recent drone sightings in Poland, along with a swathe spotted around critical infrastructure across Europe, including in Belgium and Denmark, have sparked fear across some Nato countries.

Now, there is talk that a "drone wall" is to be designed to protect parts of Europe - but just how necessary is this, really? And more pertinently, how realistic?

A wake-up call to Europe

On 9 September, around 20 Russian drones overshot Ukraine and flew into Poland, forcing the closure of four airports.

Nato jets were scrambled and several of the drones were shot down - the rest crashed across Poland, scattering debris in multiple regions.

This was a wake-up call to Europe, marking one of the largest and most serious breaches of Nato airspace since the war in Ukraine began.

Which is why discussion about a possible drone wall seems ever more pressing.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesOn 9 September, around 20 Russian decoy drones flew into Poland

"This momentum really driven by these recent incursions," explains Katja Bego, senior research fellow in the international security programme at Chatham House think tank.

Drones - or to give them their official title, Uncrewed Aerial Systems (UAS) or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) - have already transformed the battle space.

On the killing fields of eastern Ukraine, they tend to be small short-range ones, typically measuring around just 10 inches, and they carry lethal explosive devices.

But these are not currently the threat to the rest of Europe. It is the larger drones - some of which can potentially fly well over 1,000km - that are fuelling calls for a European drone wall.

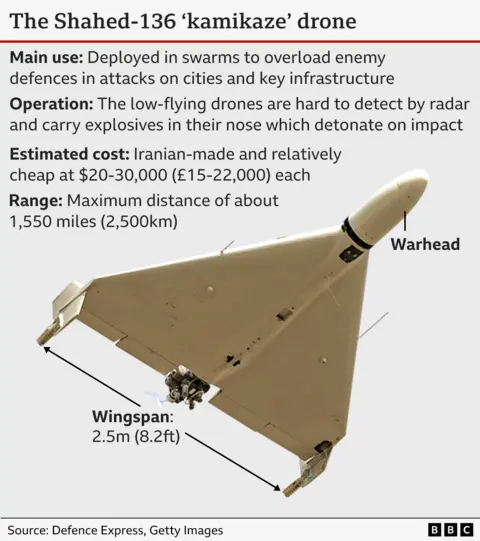

Previously Russia imported a type known as Shahed 136 drones from Iran but now it produces its own version: the Geran 2. Some Gerans were among the drones that flew into Poland in September.

So, what, some are now asking, if Russia one day sent over 200 drones? Or, say, 2,000? How would Nato respond - and in fact, could it respond?

After all, deploying fighter jets each time would be expensive. André Rogaczewski, CEO of Netcompany, a Danish IT services firm that builds digital systems for European governments, argues: "[It] is neither effective nor a sensible use of taxpayers' money."

A plague of mysterious drones

Ukraine has stepped up its own long-range drone attacks on Russian airports and critical infrastructure like petrochemical plants, bringing the war home to ordinary Russians.

Then there are sea drones: uncrewed vessels that can travel either on or below the surface, as used with devastating effect by Ukraine against Russia's Black Sea fleet.

But there is something that is in some ways more sinister than clearly identifiable drones used by countries that are openly at war.

That is: the plague of mysterious, anonymous drones that have appeared.

Sometimes these turn up in the dead of night, around Europe's airports, including one in Belgium's main airport near Brussels earlier this month. There have also been similar sightings in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany and Lithuania.

Unlike the clearly identifiable Russian attack drones in Ukraine, these "civilian drones" in Western Europe have not – so far – been armed with any explosives. But being anonymously launched, it's hard to prove where they come from or who activated them - or indeed if they are being launched from passing ships.

Suspicions fall on Russia with Western intelligence officials believing Moscow is using proxies to launch these short range drones locally to cause havoc and disruption. The Kremlin denies any responsibility.

Belgium is one significant target, as the home to Nato headquarters, the European Union and Euroclear (the financial clearing house that handles trillions of dollars of international transactions).

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images'From a European perspective, there is only one country… willing to threaten us and that is Russia,' argued Denmark's Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen in October

There is an ongoing debate around whether Europe should release around €200bn worth of frozen Russian assets, held in Belgium, to help Ukraine. So is it a coincidence that mystery drones have appeared around Brussels and Liege airports, as well as a military base?

The UK has sent a team of counter drone specialists from the RAF Regiment, deployed from RAF Leeming in North Yorkshire, to help bolster Belgium's defences against the drones.

Still, the mystery drones are worrying: both because of the danger posed to aircraft as they take off and land but also because of the risk of surveillance, especially around military bases and critical infrastructure such as power plants.

Drone wall: why it's not a silver bullet

The plan for a drone wall is Europe's response to the threat of cross-border incursions by drones launched specifically from Russia.

The wall has been described as an integrated, coordinated, multi-layered defence system stretching initially from the Baltic states to the Black Sea.

It's likely to comprise a combination of radars, sensors, jamming and weapons systems to detect incoming drones - and then to track and destroy them.

EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas has said a new anti-drone system should be fully operational by the end of 2027.

Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Global Images Ukraine via Getty ImagesRussia originally imported a type of drone known as Shahed 136 drones from Iran

Not surprisingly, those countries keenest to see it deployed quickly - including Poland and Finland- are those geographically closest to Russia.

Katja Bego believes it is necessary - and long overdue.

But she adds: "This is not just about drones. There is really not enough in place in terms of more traditional missile defence, air defence, along the Eastern flank borders."

Nonetheless, a drone wall is not a silver bullet for air defence. And others aren't convinced it's entirely realistic.

Robert Tollast, a research fellow at Whitehall think tank The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), argues that the idea of some "sort of impervious wall", is, in his words, out of the question.

Yet he can still see why there are calls for it and wants to try.

Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Global Images Ukraine via Getty ImagesPeople in Kyiv and other cities across Ukraine are facing the consequences of attack drones

"For countries that are close to the Russian border – the Baltics, Poland, Germany as well because of course they're within range of those long-range drones - it is absolutely essential to try and build something like this," he says.

"The idea here would be not so much to actually build a full-on wall, or something that's fully impenetrable", agrees Ms Bego.

"It's not really possible - both in terms of the length and also just the available technologies are not 100% foolproof... But rather you're looking at a combination of things that hopefully can capture different types of drones and stop them."

Stopping drones: Hard kills vs jamming

Fabian Hinz, a research fellow at The International Institute for Strategic Studies in London describes a whole menu of options to detect drones.

"You can have acoustic detection; airborne radars that can detect low flying targets really well; ground-based radars that have very short ranges against low-flying targets but [that] still work really well against high flying targets.

"You can have optical systems, infrared systems - and once the detection is done you have either soft kill or hard kill."

Hard kill means destroying the drone, either with gunfire or missiles. Soft kill means making an incoming drone ineffective, usually through electronic means.

EPA/Shutterstock

EPA/ShutterstockPeople look at debris of a Geran-2, among destroyed Russian military equipment on display in Kyiv

Russia and Ukraine have been able to get around soft kills on the battlefield by packing their drones with tens of kilometres worth of fibre-optic cable that spools out as it flies, but that's not an option for something travelling hundreds of kilometres across borders.

As for hard kills, Mr Hinz describes many ways of achieving them: from surface-to-air missiles to fighter jets and helicopters.

"You can have lasers which could be useful as well," he adds, "but [these] are not quite the one the wonder weapon people make them out to be."

André Rogaczewski believes jamming can be effective as an alternative. Ultimately, however, for any drone wall to be effective, it needs to be able to deal with a wide variety of aerial threats, possibly all coming at once.

A financially controversial question

As tensions between Europe and Russia have risen since Moscow's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, so too have other incidents of so-called "hybrid" or "grey zone" warfare attributed to Russia, which in most cases denies them.

These include cyber attacks, disinformation campaigns, incendiary devices inserted into cargo depots, surveillance and sometimes sabotage of undersea cables.

And yet at a security forum in Bahrain earlier this month, Admiral Giuseppe Cavo Dragone, the Italian chairperson of Nato's Military Committee, told me that of all Nato's defence needs right now, air defence is the top priority.

Anadolu via Getty Images

Anadolu via Getty ImagesAdm Giuseppe Cavo Dragone sais that of all Nato's defence needs right now, air defence is the top priority

The first stages of the drone wall are due to be activated within months, though not all details have been finalised.

Meanwhile, Nato's Allied Command Transformation (ACT) based in Norfolk, Virginia is working on longer-term solutions. This is not an easy challenge.

Mr Tollast says the main challenge of the drone wall is the sheer scale of the area which needs to be protected. "You need a huge range of tactical radars for low flying drones and larger radars for higher altitude targets, across thousands of kilometres.

"And you need cost effective interceptors and forces to be ready around the clock. It will never be watertight, and even as costs of some radars and interceptors fall, it's very unlikely to be cheap."

Russia's attacks have ramped up - Ukraine is fighting to hold on through another winter

How China really spies on the UK

COP30: Trump and many leaders are skipping it, so does the summit still have a point?

The question of finance is a complex one. "It is a really difficult defence question," says Mr Tollast. "Even with rising European defence expenditure, there's still going to be a lot of competition from other sectors in defence [for that funding] - we need more ships, submarines, nuclear weapons even, satellites as well.

"So this is why a drone wall will remain this sort of slightly financially controversial issue for some people."

It will potentially be funded from a mixture of EU money, national budgets (especially in Eastern Europe) and interest from frozen Russian assets.

Initially, says Ms Bego, the drone wall referred to defences across the Eastern flank, but since the the EU has been spearheading this, they've been expanding it.

"Everyone recognises something needs to happen and there is a need to co-ordinate this and to mobilise money for this, but the who and what is very much under discussion...

"The more foolproof you would want it to be, the more expensive it gets".

As for the target date, Mr Tollast believes 2027 is very ambitious - but adds, "they can definitely achieve more protection by then".

Shoot the archer, not the arrow

While all of this is going on, the task of building the wall is becoming ever harder. Because as fast as new counter-drone measures are introduced, up pops a new form of drone threat that can overcome them.

This all makes it something of a new arms race.

"The development cycles for technologies in this space are hyper-accelerated, above all in conflict environments," says Josh Burch, co-founder of Gallos Technologies, a UK-based company that invests in security technology.

"It means that any defence against drones will rapidly be rendered outdated as aggressors adjust.

"The aggressor", he concludes, "will observe, adjust, repeat – until they get through".

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesMany have died or been wounded in Ukraine from Russian drone and missile strikes

So are we asking the wrong question altogether? Rather than building a drone wall to stop the drones, is it better to target the bases launching the drone themselves - as the old saying goes, shoot the archer, not just the arrow.

"It's one thing to become more resilient against it, but it would be much better if it did not happen at all," argues Ms Bego.

"And that's really around making it much clearer to Russia, or whichever actor is behind this, that this kind of behaviour crosses the line. It has consequences and comes with the costs for them. And that's important. It should really be part of this."

But any suggestion of Nato hitting Russian targets – kinetically, as opposed to digitally in cyberspace – would be incredibly risky and escalatory.

Ever since Russia carried out its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 the challenge for Nato, and especially its most powerful member the US, has been to help Ukraine to defend itself but without getting drawn into a Nato-Russia war.

Building a defensive drone wall in Europe is one thing. Attacking the places where those drones are launched from is quite another.

Top picture credit: Getty Images, Sketchfab

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.

You must be logged in to post a comment.