It takes balls to title your book Notes on Being a Man. And, superficially, Scott Galloway could easily be lumped in with a dozen other manosphere-friendly alpha-bros promising to teach young men how to find their inner wolf. He is, after all, a wealthy, healthy, white, heterosexual, shaven-headed, 61-year-old Californian who made his name and fortune as a successful investor and podcaster.

But in reality, he is almost the opposite: liberal, left-leaning and surprisingly sensitive. The guy who advises his readers on “how to address the masculinity crisis, build mental strength and raise good sons” has been described as a “progressive Jordan Peterson”, or “Gordon Gekko with a social conscience”.

Galloway is also sufficiently self-aware not to claim he has all the answers. “I don’t think it would be well received for me to say, ‘This is how you become a man,’” he says, speaking from his London home. “What I’m trying to say is, this is where I’ve had some success, and mostly where I screwed up trying to become a man.”

He moved to the UK from Florida three years ago, partly because he and his wife thought it was a better place to raise their two sons, who are now 15 and 18. “Great culture, interesting people, the proximity of the continent is amazing, and the Premier League is just fantastic – there’s nothing like it.” Also: “If you’re talking about assault rifles or bodily autonomy, it’s not even a discussion here.” He still finds the weather challenging, though.

There’s a studio in the basement where Galloway records his popular podcasts: Prof G Pod (business and life wisdom – and he really is a professor, of marketing, at New York University); Raging Moderates (with the liberal Fox News host Jessica Tarlov); and most popular of all, Pivot, with tech journalist Kara Swisher. The two of them are good company, comparing their jetset lifestyles, commenting on tech, politics and current affairs, their easy banter peppered with Galloway’s wilfully crude jokes. “We can rib each other,” he says, “because that’s a form of equality and affection.”

‘Raging Moderates’ Scott Galloway and Jessica Tarlov in New York in April. Photograph: Cindy Ord/Getty ImagesWhen Galloway first started talking about masculinity, he says, people weren’t prepared to listen. “It was like, here’s more misogyny, here’s more men blaming women – the gag reflex was so strong.” This was about four years ago, but all that has now changed. When Notes On Being a Man was released in early November, it raced to the top of the New York Times advice books bestseller list and Galloway has been in demand in the media ever since, giving his take on what’s wrong with men, and what to do about it.

Galloway has plenty of statistics to back up his claim that young men really are in trouble. Drawing on research by writers such as Richard Reeves (author of 2022’s Of Boys and Men) and his NYU colleague Jonathan Haidt (whose recent book The Anxious Generation sounded the alarm on social media), he sketches out a landscape of rising rates of everything from boys’ school suspensions to male unemployment, addictions, loneliness, and failure to complete college. “We’re going to graduate probably two women for every one man from college in the next five years, because men drop out at a greater rate.”

https://media.gutools.co.uk/images/1ba7dde5682d9561a2818310deb1531b6b429474

Galloway suggests that the previous denial of the problem, especially by the political left, might even have put Donald Trump back in the White House. “Let me offer that the reason we elected [him] is because of struggling with men.” Two groups that pivoted hardest towards Trump in 2024, he says, were young men, and women aged 45 to 64, and “my thesis is that’s the mothers of young men.” While Trump embraced the manosphere, the Democrats championed the interests of virtually every special interest group except young men, he argues.

In his book, Galloway’s solutions to men’s problems often boil down to a set of pithy codes and maxims, some of which feel like sound common sense, while others might feel rather old-fashioned. One of his oft-repeated tenets, for example, is that “men protect, provide, and procreate”. You could easily say the same of women. Also, Galloway tends to see the “protect” element in the context of men using their physical strength for good – “real men don’t start bar fights; they break them up” – even if a lot of the time, the thing people need protection from, especially women, is other men.

And the “provide” element he couches largely in economic terms. “I tell my sons, when you’re in the company of women, you pay for everything. And if you can’t, you don’t go out … A woman is not going to have sex with a man who splits the bill with her.” Signalling resource is one of the three things women find most attractive, according to another of his maxims, along with kindness and intellect. He admits his sons tell him this is a boomer view of modern dating, but “I try to go where the data takes me,” he says. “Research shows that society, and men themselves, are really hard on men when they’re not economically viable.”

A woman is not going to have sex with a man who splits the bill with her

And if men aren’t economically viable, that’s when the problems start, he contends. “They’re just going to have an absence of mating opportunities. And when men don’t have a romantic relationship, they tend to kind of come off the tracks.” He cites statistics that women fare much better without men than vice versa. “Men have a difficult time maintaining friendships without a romantic partner. They tend to reallocate that energy into conspiracy theory, going extremely online, porn – and they never develop the skills to establish a romantic relationship.” Galloway has been highly vocal about the tech industry and social media’s role in compounding these problems, by giving men easy dopamine hits and fewer reasons to ever leave their bedrooms. As he puts it, “I worry we are literally evolving a new breed of asexual, asocial male.”

Galloway’s analysis can become somewhat Darwinian and reductive – a little bit, “men are this and women are this”, as if there’s a one-size-fits-all set of solutions to these problems – coloured by nostalgia for a bygone patriarchal order. Nuances of race or sexuality are barely addressed, as Galloway readily admits: “People say, well, what’s the masculinity code for gay men? And the honest answer is, I have no fucking idea. I’m not even gonna take a swing at it.”

But isn’t it also a bit … Jordan Peterson? Peterson proposed his own cure for “the masculinity crisis” in his bestselling 2018 book 12 Rules for Life, which received as much ridicule as it did praise – rule number one was “stand up straight with your shoulders back”. And we’ve had plenty of masculine self-help books in this mould since. Galloway has a surprising respect for Peterson, not least for broaching this subject before it became fashionable. “Where we differ is that I find that Jordan basically uses his incredible skills of communication and knowledge of psychology to always reverse-engineer into an incredibly conservative viewpoint that sometimes, in my view, takes women’s rights away. That it basically goes back to this notion of ‘women are happiest when they’re in a supporting role to men’. I just don’t think that’s accurate.”

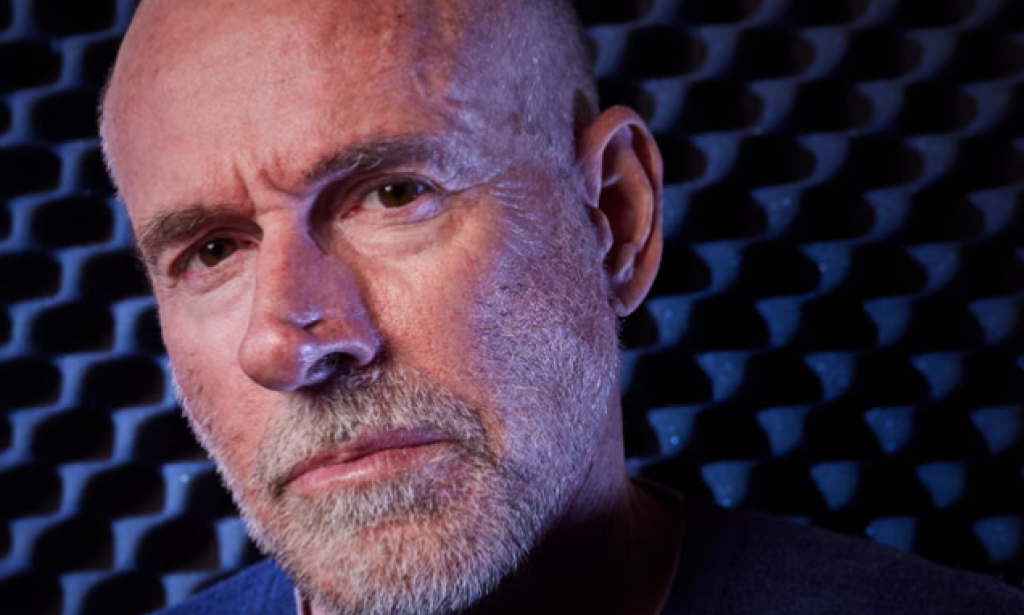

Galloway in his podcasting studio: ‘I’m not saying that women need to lower their standards. I think men need to level up.’ Photograph: David Levene/The GuardianGalloway is at pains to point out that he’s not blaming women for men’s problems. “I do not think the answer is to in any way economically disadvantage women,” he says. “I’m not trying to repackage violence here and say that women need to lower their standards such that we don’t have a bunch of angry men out there. I think men need to level up. And I think, as a society, we need to implement more programmes to level up all young people.”

Given all this, you wonder why he chose to focus just on men. Beyond his book – in his TED Talk last year, for example – Galloway has persuasively argued that the real problems facing all of society, especially in the US, are the transfer of wealth and power from the young to the old, and the commercialisation of politics, healthcare and higher education. When it comes down to it, he says, “this is a battle between liberal and illiberal, it’s not a battle between men and women. The genders have done a great job convincing themselves it’s the other gender’s fault. I just don’t think that’s productive.”

Where Peterson and his ilk seek to trace men’s problems back to the erosion of conservative values, Galloway does some reverse-engineering of his own: back to a place of economic, romantic and especially family security. If there’s a moment “when a boy comes off the tracks and develops problems later in life”, he says, “it’s the moment he loses a male role model through death, divorce or abandonment”. The thesis is more personal than his data-driven approach suggests.

What Trump and guys like Elon Musk are doing could not be more anti-masculine

Galloway’s own father and mother emigrated from Scotland and England, respectively, and settled in California in the 1960s, but their American Dream did not last. When Galloway was nine, his father walked out and moved in with another woman, leaving his impoverished mother to bring him up alone. Not exactly a role model, then, but his father, Galloway’s grandfather, was even worse, he says – an angry alcoholic. “When my dad was a very young boy, his father used to come home and wake him and beat him.” It’s a low bar, Galloway admits, but at least his own father was an improvement.

Their relationship taught him a lot, he says. One of his biggest breakthroughs was when he realised that he kept a score card around relationships, starting with his dad. Like, “Why am I being such a good son when he wasn’t that good a father?” He says he became much happier when he put the score card away and just focused on being the son he wanted to be – and the husband, partner, friend, co-worker he wanted to be, on his own terms. It’s made him happier and his relationships better, he says. His father died earlier this year. “My dad softened as he got older, and we had a wonderful relationship the last 20, 30 years of his life.”

When Galloway tells his origin story, he does not paint himself as an exceptional talent. He was unremarkable academically and physically, better at scoring weed than picking up women, it seems. He puts his success as much down to luck and structural advantages: good schooling in a prosperous state in a prosperous country, not being subject to racial or gender discrimination, a loving mother, scraping into a good university (the University of California, Los Angeles). “The truth is, I was born on third base.” But having grown up relatively poor, economic security was always his motivation. “I took a very much like, ‘How do you win capitalism?’ approach.”

Pivot Live with Kara Swisher in Austin, Texas earlier this year. Photograph: Chris Saucedo/SXSW Conference & Festivals/Getty ImagesHe was also fortunate to hit his stride as an entrepreneur just as the dotcom boom was beginning, and founded some successful (and some unsuccessful) companies in emerging fields such as e-commerce and digital market research. In 2017 he sold his business intelligence firm L2 for $155m (he estimates his own net worth at about $150m (£117m)).

Now Galloway divides his time equally between writing, investing and media, including his podcasting network. He is happy in London, but is planning to return to the US next year “to make America America again”. In preparation for the 2026 and ’28 elections, he wants to help build an informal, Democrat-friendly podcast network, and is already working with several Democratic candidates. “People hear all these celebrities talking about how they’re going to leave America. I actually think, when your country isn’t doing well, that’s when you’re supposed to go home.”

Whether or not a crisis among men led to the current regime, the men now in power are definitely not the manly paragons Galloway has in mind. “I would argue that what Trump and guys like Elon Musk are doing could not be more anti-masculine,” he says. “They have conflated, or tried to conflate, masculinity with coarseness and cruelty. And it’s not only incorrect, it’s a terrible role model for young men.”

Who are Galloway’s role models? The first two he offers are Muhammad Ali and, more surprisingly, Margaret Thatcher. “I don’t know if it’s fair to call her masculine, but I think that kind of strength …” He’s also an admirer of Keanu Reeves, who “gives a lot of his exceptional compensation to other actors, is super kind, donates time, very humble”.

Is Galloway a good role model? He’s not so sure. “People say, ‘Oh, your kids are so lucky to have you,’ and I get self conscious because there are so many weekends where I’m so wrapped up in my own shit and not spending enough time or attention with my kids. I’m not present enough. So I have huge impostor syndrome around this.”

We live in a modern society where people are not going to kill you because you cry, and it just feels really good

For all his life lessons, Galloway is not afraid to admit his own fallibility and vulnerability. When his father died earlier this year, for example, he spoke movingly about it and wept on his Pivot show. Crying is good for men, he argues. “For the last 3,000 years, we’ve been taught if you demonstrate weakness – and a way to demonstrate weakness is crying – that some other dude might take your shit, fuck your wife and eat your children. And so men have been taught to not express that weakness. And the good news is, we live in a modern society where people are not going to kill you because you cry, and it just feels really good.”

He didn’t cry between the ages of 29 and 44, he says. Now “I don’t have anything that [holds] me back from crying. And it’s not an attempt to demonstrate my femininity, it’s just an attempt to slow time down.”

Despite his rigorous fitness regime, his access to luxury experiences and cutting-edge healthcare (including regular testosterone injections), and his embrace of a certain amount of hedonism (he likes his cannabis edibles, he happily declares), Galloway is starting to feel his age.

“When you hit about your late 50s, years turn into seasons, seasons turn into months, months into weeks, and it’s like, ‘Fucking A, the end is barrelling towards us.’ And one of the tricks I found for slowing it down is if you find something that inspires you and really moves you, stop and feel it, and touch it. I walked in Regent’s Park yesterday, and there’s this rose garden there I’d never seen. I’m not into roses, but I just thought, God, this is so cool. So I just stopped and thought, why do I find this interesting? Who does this? Why do they do it?”

He gets emotional every other day now, he says, “in the context of watching Modern Family, or reading something that moves me, or hearing a friend talk about the struggles with their kids. And I’ve generally found that it informs your own emotions, it makes you feel closer to people, and that, for the most part, people are really receptive to it.” Especially other men. Rather than wanting to take his shit away, he says, “they’re like, Jesus, can I have some of that?”

Maybe this openness to emotion is what really sets Galloway apart from his testosterone-fuelled peers. You can model the alpha-male lifestyle and dispense codes and maxims, but it still takes balls to admit it’s good for guys to cry.

Notes on Being a Man by Scott Galloway (Simon & Schuster Ltd, £22). To support the Guardian, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.

At this unsettling time

We hope you appreciated this article. Before you close this tab, we want to ask if you could spare 37 seconds to support our most important fundraising appeal of the year.

In his first presidency, Donald Trump called journalists the enemy; a year on from his second victory, it’s clear that this time around, he’s treating us like one.

From Hungary to Russia, authoritarian regimes have made silencing independent media one of their defining moves. Sometimes outright censorship isn’t even required to achieve this goal. In the United States, we have seen the administration apply various forms of pressure on news outlets in the year since Trump’s election. One of our great disappointments is how quickly some of the most storied US media organizations have folded when faced with the mere specter of hostility from the administration – long before their hand was forced.

While private news organizations can choose how to respond to this government’s threats, insults and lawsuits, public media has been powerless to stop the defunding of federally supported television and radio. This has been devastating for local and rural communities, who stand to lose not only their primary source of local news and cultural programming, but health and public safety information, including emergency alerts.

While we cannot make up for this loss, the Guardian is proud to make our fact-based work available for free to all, especially when the internet is increasingly flooded with slanted reporting, misinformation and algorithmic drivel.

Being free from billionaire and corporate ownership means the Guardian will never compromise our independence – but it also means we rely on support from readers who understand how essential it is to have news sources that are immune to intimidation from the powerful. We know our requests for support are not as welcome as our reporting, but without them, it’s simple: our reporting wouldn’t exist. Of course, we understand that some readers are not in a position to support us, and if that is you, we value your readership no less.

But if you are able, please support us today. All gifts are gratefully received, but a recurring contribution is most impactful, helping sustain our work throughout the year ahead (and among the great benefits, it means we’ll show you fewer fundraising requests like this). It takes just 37 seconds to give. Thank you.

- Far fewer asks for support

- Ad-free reading on all your devices

- Unlimited access to the premium Guardian app

- Regular dispatches from the newsroom to see the impact of your support

- Unlimited access to Feast, the Guardian recipe app

You must be logged in to post a comment.