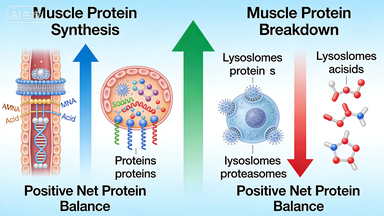

Muscle tissue is in a constant state of flux each day, with the rates of muscle protein synthesis (MPS) and muscle protein breakdown (MPB) continuously shifting. Net protein balance refers to the difference between these two processes. To build muscle, you need to tip the scales in favor of MPS over MPB, creating a positive net protein balance. Both resistance training and strategic nutrition—specifically intake of essential amino acids—are key to boosting muscle protein synthesis rates.

What’s the Best Workout for Muscle Growth?

Resistance training is unequivocally the most effective form of exercise for building muscle mass. When it comes to training load and muscular failure (the point where you can no longer perform a repetition with proper form), research shows nuanced effects based on how heavy you lift:

For moderate to high-load training (60–90% of your one-repetition maximum, or 1RM), training to failure has little to no impact on muscle growth outcomes.

For moderate to low-load training (30–40% of 1RM), pushing to muscular failure is essential to maximize muscle gains.

Training frequency also plays a minor role in muscle growth when total training volume is kept the same—this means you can structure your workouts around your schedule as long as you hit your weekly volume targets. That said, higher training frequency (e.g., training each muscle group three times per week) offers benefits when following a high-volume training plan.

How Does Diet Impact Exercise Performance & Muscle Growth?

Sufficient calorie intake is critical for optimizing exercise performance and physical capacity. Being in a calorie deficit during training can lead to a host of issues, including accelerated muscle breakdown, slow recovery, reduced bone mineral density, mood disturbances, and even menstrual dysfunction in female athletes. Maintaining a calorie surplus after resistance training is a key driver of muscle growth.

It’s not just total calories that matter—carbohydrate intake is equally vital, as carbs are the body’s primary fuel source for exercise. Extensive research confirms that tailoring carb intake to your exercise demands boosts endurance and performance in high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Protein intake is non-negotiable for muscle synthesis and recovery: consuming protein post-workout is essential to achieve and maintain a positive net protein balance.

What Energy Systems Power Muscle Contraction?

Muscle contraction relies on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for energy, and the body has three distinct energy systems that kick in based on the type, intensity, and duration of exercise:

ATP-PC System: The body’s fastest energy source, using stored ATP and phosphocreatine for short, explosive bursts of movement.

Anaerobic Glycolysis System: Produces energy by breaking down glucose without oxygen, and is the primary cause of lactic acid buildup—one of the main contributors to muscle soreness.

Aerobic Oxidation System: The slowest of the three systems, but the most sustainable, using oxygen to break down carbs, fats, and proteins for long-duration, low-to-moderate intensity exercise.

Can Weight Training Turn Fat Into Muscle?

Weight training can increase muscle mass and reduce body fat, but these are two entirely separate physiological processes—fat cannot be directly converted into muscle.

What Are the Key Benefits of Weight Training?

Weight training builds muscle by creating micro-tears in muscle fibers; these micro-tears send signals to the body to use dietary protein to repair and rebuild muscle tissue, with carbohydrates and fats providing the energy needed for this process. It also reduces body fat by tapping into stored fat reserves to fuel muscle growth and the energy demands of training itself.

The reason fat can’t turn into muscle boils down to basic biology:

Fat is composed of triglycerides—molecules made up of a glycerol backbone and three fatty acid chains, consisting almost entirely of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen.

Muscle tissue is a complex mix of muscle fibers, glycogen, water, and small amounts of intramuscular fat. Muscle fibers are built from amino acid chains, which contain nitrogen—a nutrient that is almost exclusively stored in muscle tissue in the human body.

There is no biological mechanism in the body that can rearrange fat molecules into amino acids, and fat lacks the nitrogen required to form muscle proteins. While the body can perform transamination (rearranging amino acids to form new ones), there is no evidence that amino acids can be synthesized from non-amino acid sources. Nearly all muscle growth relies on dietary nitrogen, and dietary protein is the only significant source of nitrogen in the human diet.

In short: weight training drives both muscle gain and fat loss, but these processes occur independently of one another.

You must be logged in to post a comment.